It’s Belfast in the 1980s, and our main character lives in the Holyland neighborhood, where there may be a bomb on her doorstep, hidden in a gym bag that she nearly trips over on her way out to look for a rumored house party.

She is the kind of person who can interpret this world for you, but what’s important to her is listening to the right bands, and wearing the right clothes.

She tries to restrict what she eats, but if she sees something good she will eat it when no one is looking, even if they have thrown it away and she has to retrieve it from the trash. She will throw it up later.

There are young men around, romantic prospects, and the getting-to-know-you involves decoding the signs that this guy might be a Protestant who is trying to hide it from the cute Catholic girls he’s flirting with. And as these young people search for the house party, they will be detained by the authorities, who patrol the streets of the city in armored military vehicles.

This is the work of Fiona O’Rourke, who I was in a writing group in Dublin with. I got very invested in it the way you can get when you read somebody’s stuff all the time and watch it evolve. But Fiona was told by Irish publishers, when shopping her novel around, that no one wants to read about the Troubles.

In the years since, the success of the show Derry Girls shows that people love the juxtaposition of teenagers in 80s fashions being late to school because soldiers have boarded their bus for security checks. Sometimes publishers are wrong about the things nobody wants to read.

Fiona was telling me recently about a course she leads at the Irish Writers Centre called Writing the Troubles. It’s a Zoom course, with participants calling in from all over. Most of them have lived experience of the Troubles, but some no longer live in the North. All of them, herself included, have felt like outsiders who need someone to give them permission to write about this subject. Fiona feels this way herself, having left the North while the conflict was still ongoing, tired of living with the constant threat of violence.

When I read fiction about a conflict, the author is usually writing to me across both time and culture, and I’m in a certain mindset when I begin reading. So I was surprised when Fiona mentioned a few of the published stories she’s asked course participants to read, and the writers she named were living people whom she and I know in real life.

I emailed her afterward to ask about how it is different, teaching students who have a personal connection to an event of world historical significance, and assigning readings by authors they could run into on the street, compared with assigning canonical stuff that might make the subject feel distant and final.

She said she is always updating a list of recommended reading for course participants, which includes old and new works, and that she invites some of the contemporary writers to join class meetings over Zoom. The guests read from the work, followed by open Q&A. “I set it up in such a way that everyone on the zoom was equal with no ‘spotlighting’ of guests which causes separation from the audience, but all writers together on the screen in the little zoom boxes. I believe this bringing together of the reader/writer and the recommended author helped endorse and authorise the right to write the Troubles.”

If this sounds good to you, I see that the next section is scheduled to begin in September, and it’s open to writers around the world, including those who don’t have a personal connection to the conflict. Or, if you’d just like some recommendations for further reading, she shared this list by Irish writer Maria McManus. I hope that sometime we get a novel from Fiona to add to this list.

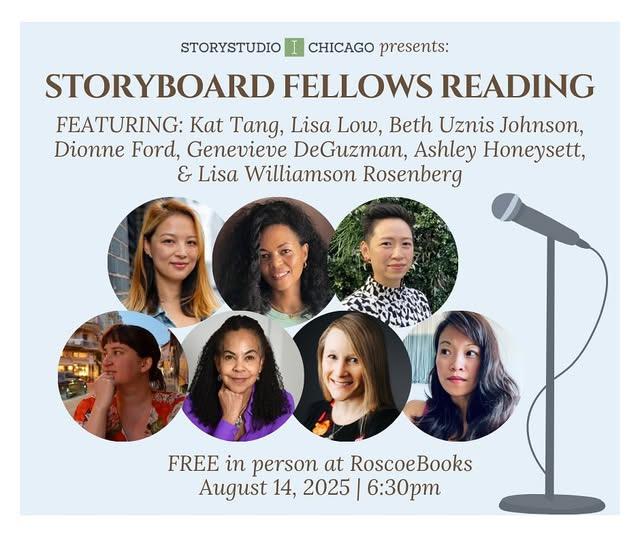

Chicagoland friends, I will be part of a group reading at Roscoe Books on August 14 at 6:30 PM. Come join us!

Fantastic list you shared in the link! I loved Wendy Erskine's Sweet Home so much! One of my favorite story collections.