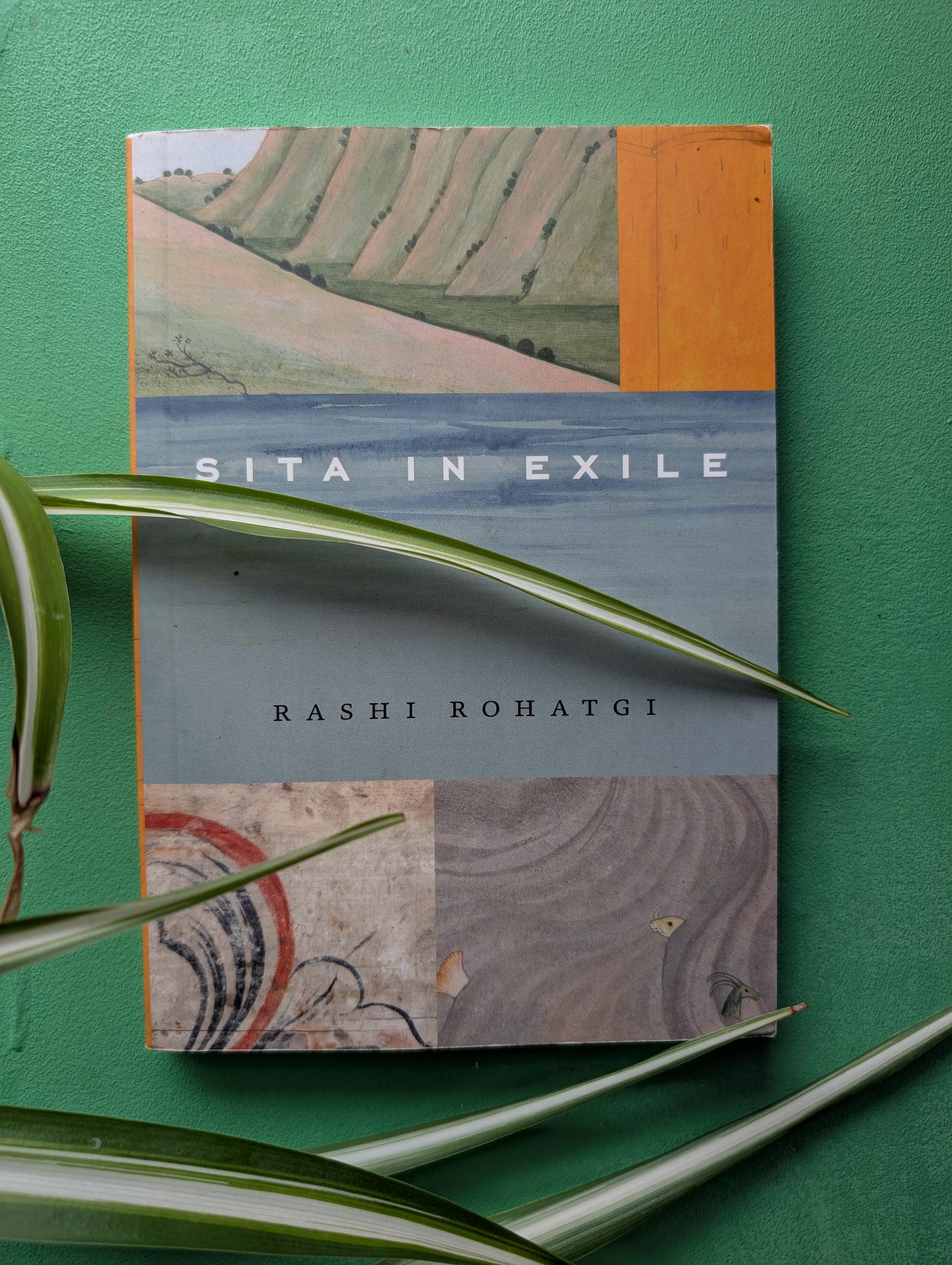

When I read Rashi Rohatgi’s book Sita in Exile, I read a depiction of the lives of American kids of Indian descent that I’d never seen before. Rohatgi’s focus is not on the contrast between the girls’ home lives and the American culture around them. It is on their relationship to Hinduism, which is intense and fraught.

The best friends at the center of Sita in Exile, both so intensely engaged with Hinduism, engage in different ways. Sita ritualistically observes the holidays, which pass unnoticed within her own family (her husband is not Indian, they are isolated from their families by distance and COVID, and their child will not inherit her culture unless she makes it happen), and among the Norwegians around her. Bhoomija, an artist, is irreligious and irreverent, and much of her work either critiques Hinduism or uses Hinduism as a lens to critique other things.

Bhoomija’s artistic irreverence toward the Hindu stories that inspire her has somehow gotten her into legal trouble, and she’s desperate for Sita to come back to the US from Norway, where she has settled down with her husband and child, and be with her. Sita repeatedly uses the word “summon” to describe Bhoomija’s call, as though Bhoomija has supernatural power over her. And it seems that if Sita responds to the call, it won’t be a normal visit. She will abandon her family and never return.

I love this depiction of best-friendship as a call that might demand too much.

Do other books like this not exist, or have I just not read them? Over a few rounds of questions and answers by email, Rohatgi gave me a slew of recommendations, which I will be sharing with you over the next few posts.

ME: Your novella Sita in Exile is a retelling of the Ramayana from the point of view of one of its female characters. When I was in India last year, prowling the bookshops (as I like to do when on vacation in a new place), I saw that there is a whole cottage industry devoted to retellings of the Ramayana from the point of view of Sita, her sister, and other supporting characters. Most of them look like popular fiction--they are pitched to women readers, the point is to humanize the female characters who have been underexplored, and the emphasis is on storytelling and emotional appeal more than on virtuosic writing or other formal aspects of the books. Do you know the types of books I'm talking about, and is it appropriate for me to lump them all into the same category? Have you ever seen them for sale outside of India? Have you read any of them? Do you like what they are doing, and do you feel like they have anything to do with your book? Are trying to do any of the same things you were trying to do with Sita in Exile, or do you feel like your concerns are different?

ROHATGI: Yeah, there are many Sita books! Until the advent of e-books, it was very hard for me to find these books outside of India, and because there is no e-book version of Sita in Exile, I imagine that it is similarly difficult for the primary readership of Sita books to find my book inside India. But I would consider all of these as coming from the same literary lineage, written largely by women who’d heard various formal versions of the story – in traditional recitations, in childhood storytime, in dance dramas – but were also steeped in comic book, television, and cinematic retellings of Hindu mythology more widely alongside what I’d call a healthy appreciation for reading that spills beyonds the canonical. I’d center our common ground in a shared love for the golden trifecta of emotionally-grounded Hindu mythological retellings: Devdutt Pattanaik, Kavita Kané, and Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni. These three authors are themselves quite distinct from one another, so I think your question about whether this category exists is useful insofar as it flags that it’s a category that can be disaggregated further, for sure – and although I’d place Sita in Exile within it, my favorite of the books which more quintessentially encapsulates what a Sita book can be is Vayu Naidu’s Sita’s Ascent. Sita in Exile is perhaps best described as a book whose protagonist would be a reader of (though not a writer of) Sita books, where the vibe of the novella shifts to encompass some of its more literary and structural concerns.

ME: The Indian-American writers that I’ve read (Jhumpa Lahiri and Akhil Sharma come to mind) have written about Indian diasporic communities and families living in the U.S., subjects that I think are legible to people from any background who may not be very knowledgeable about Hindu traditions. But in Sita in Exile, there’s a character named Bhoomija who is a young, American-born artist whose work is feverishly engaged with Hinduism. She is irreverent to a degree that gets her in trouble, but lacking reverence is not the same thing as not caring. Do you know writers whose books are distributed in the U.S. who find Hindu traditions to be generative in this way and whose work I could read?

ROHATGI: I find it difficult to answer this question succinctly because of the ways in which American culture and Hinduism intersect in terms of literary legibility. The kinds of writing that we are taught in schools as being foundationally American – Thoreau, Emerson – are intentionally and extensively engaged with Hindu tradition. In Sita in Exile, our protagonist is living it up Walden-style, in self-imposed, privilege-caveated exile, whilst Bhoomija’s irreverence echoes Emerson’s. Vaishnavi Patel’s Kaikeyi and Amit Majmudar’s Godsong are two contemporary American works that enrich and are more richly read in the context of readers’ own engagement with American Hinduism, but I think that to some extent your question is less about philosophical underpinnings and more about cultural identity, which makes me want to focus on middle grade and young adult fiction featuring brown American protagonists grappling with the extent to which their parents’ Hinduism is meaningful to them. Supriya Kelkar’s American as Paneer Pie has that two-desi-girls-thinking-through-it structure that I love: quiet Lekha and brash Avantika; Nisha Sharma’s The Karma Map brings the romance, with bullied dancer Tara falling in love with another diasporan desi on a youth pilgrimage trip across India. I discovered both of these via writer Darshana Khiani, who curates a seasonal list of U.S.-distributed, South Asian-related kid lit – it’s an amazing list and I highly recommend poring through it.

This conversation will be continued next week. Subscribe to get it in your inbox.